Camp is, in part, a sensibility of irony and dissent – and for that reason, a potentially ripe and resonant topic for today’s social and political climate.

It is a quality that can be found in every extreme corner of our reality. From the brash excesses of late capitalism, the perilous consequences of climate change, and the chaos of politics in an asinine Trump presidency, there’s almost too much to react to with irony these days, making the topic of camp an embarrassment of riches.

What does it mean to be “camp” in our age of political absurdity, and of social media-driven of excess and spectacle? The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute will attempt to address the historical context and significance of camp in fashion for its next blockbuster exhibition.

“Camp: Notes on Fashion,” named in reference to seminal 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” by the late cultural critic Susan Sontag, will open May 9, 2019 (through Sept. 8). The news came just hours after the Institute closed “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination,” its most highly attended show to date which spawned a mass pilgrimage to see rare, never-before-seen Vatican vestments and opulent contemporary designs across two Met locations, attracting more than 1.3 million visitors in its six-month run.

While the Costume Institute has previously alternated between thematic shows and straight monographic exhibitions – the preceding year focused on Rei Kawakubo’s oeuvre and her label, Comme Des Garcons – it seems curator Andrew Bolton is looking to up the ante by tackling the particularly rich social and artistic history of camp.

More about an attitude or feeling, the term describes a breed of knowing, tongue-in-cheek irreverence. While it derives from “se camper,” the French verb for posturing, modern uses of the word “camp” source back to the early 1900s, historically codeswitch for men whose style and behavior was particularly theatrical and marginalized for having an “effeminate” quality, usually associated with gay working-class men.

Sontag was among the first to write about the ethos of Camp in a serious way, and by her account, it was distinctly a sensibility, rather than an articulated theme or prescribed style: “The essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration,” she wrote, “and Camp is esoteric – something of a private code, a badge of identity even, among small urban cliques.”

In a mix of high and low culture, Sontag saw camp in everything ranging from the idyllic, natural forms of Art Nouveau to the over-the-top costumes and choreography of Busby Berkeley films, the chintz of stained-glass Tiffany lamps, and even Tchaikovsky’s dramatic ballet Swan Lake. Today, it’s part of a proud culture that finds mainstream fans in shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race and the cult-classic films of John Waters.

Five decades on, Sontag’s description reads as a dead ringer for a coterie of contemporary fashion designers that have brought camp to a profitable luxury market with a knowing wink in recent years: Demna Gvasalia, who rose to fame with Vetements and now heads Balenciaga, is likely to make an appearance in the Met show, having turned Internet-driven irony into high art, with his 2016 collections featuring logoss ranging from DHL and Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, and a leather weekend bag aping Ikea’s 99-cent Frakta shopper.

As are the works of Moschino then and today, under Jeremy Scott’s playful eye, which has had sent sartorial interpretations of McDonalds, Spongebob Squarepants, and Barbie down the runway, not to mention a parade of green and blue-tinted model aliens dressed in prim Jackie O garb.

In an industry that thrives on statement pieces, reinvention, and topping the last trend, camp may have become synonymous with a certain class of pop-influenced fashion designers.

In addition to Gvasalia and Scott, Bolton has cited dozens of designers and historical figures – Elsa Schiaparelli, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Thom Browne, and even the “Sun God” King Louis XIV, among them – as examples of camp that will feature in the show, with a mix of approximately 175 garments, sculptures, and artworks on view in all.

With camp’s resonance in our age of Instagram, where barriers of high and art continuously mingle to the extreme – think: chunky Dad shoes, normcore, and plastic shoppers in the past few years alone – it will be a terrific thrill and a challenge for the curator and his team to determine and contextualize the most salient examples.

Sontag wrote that she was as strongly drawn to camp as she was offended by it. Often challenging norms or aping them, Camp is in large part an aesthetic of reactionary and woke dissent, and for that reason, a potentially ripe and resonant topic for our socially and politically frustrating times.

We’ve already seen its big pop influence in other areas of design. A default to the reactionary has become the norm among young interior and furniture designers, for example, who have wholeheartedly embraced the ethos and style of the irreverent, asymmetrical works of the Memphis Group, the postmodern 1980s collective led by Ettore Sottsass.

Part backlash to the dominating popularity of midcentury modern design and conservativism of the Baby Boomer generation that lived through it, the reverberating influence of Memphis can be seen in the return of exaggerated proportions, graphics, atonal colors, geometric motifs and squiggles in the work of young independent designers today.

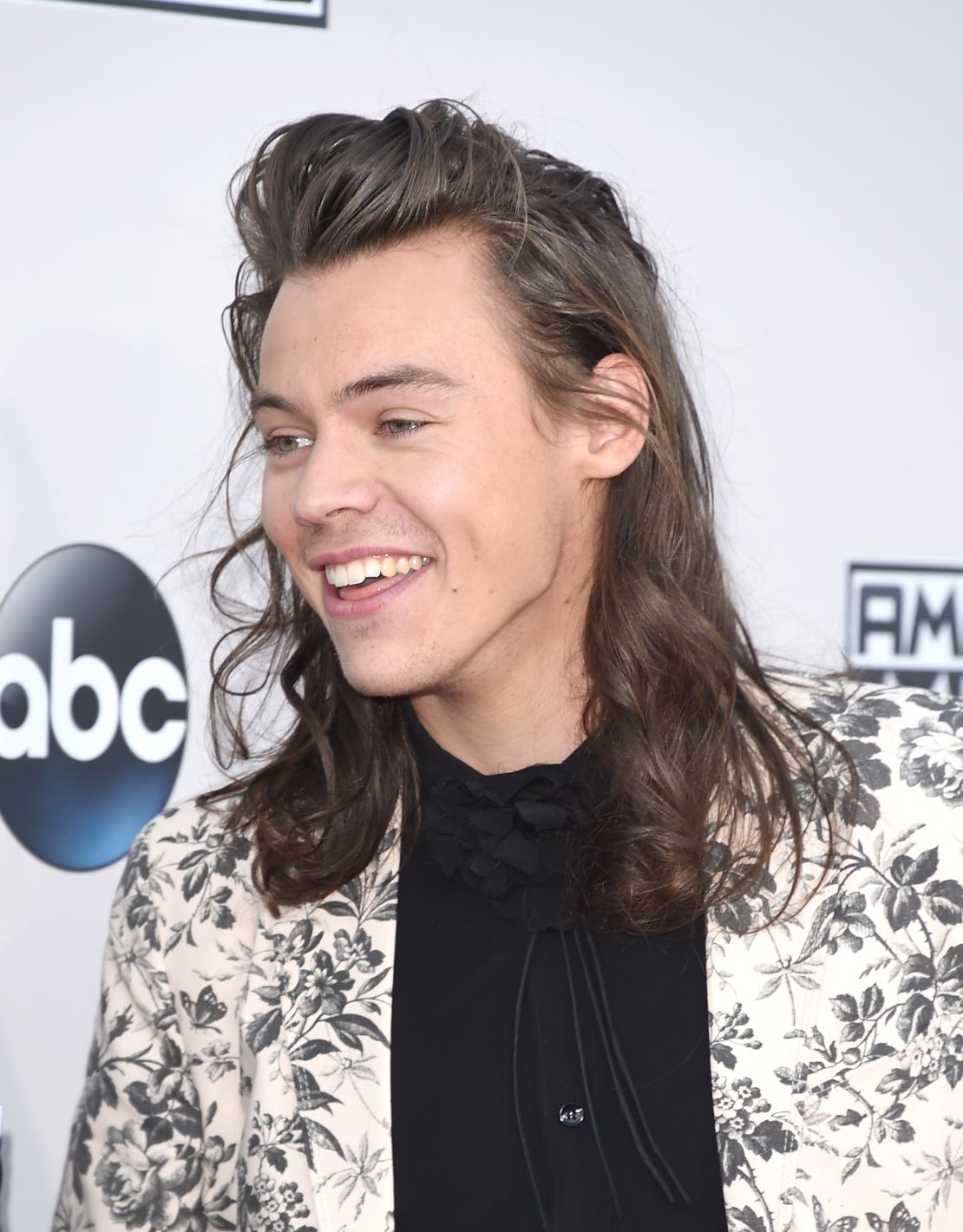

Lady Gaga, pop music’s reigning incarnation of camp, known to don outrageous designs by Jean-Charles de Castelbajac to Frank Gehry, will co-chair the Met Gala next May along with Serena Williams, who’s electrified the conservative stage of the tennis court with catsuits and Virgil Abloh-designed tutus. Harry Styles, who’s reinvented himself from a boy band member to an actor and face of Gucci’s campaign, is an apt chameleon to join as another co-chair, as will Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele.

In its most artistic and flamboyant way, “Camp: Notes on Fashion” rides the wave of cultural resistance surging across creative communities and promises to upset the applecart of neo-conservatism. And with its subversive message, we’ll only hope the exhibition will continue the triumph of “Heavenly Bodies” and avoid the failures of the Institute’s 2013 show, “Punk: Chaos to Couture,” which was fluent in its thematic choice of selections, but missed the mark in encapsulating the cultural revolution behind it.

We’ll be waiting until May for the big reveal—and the tastefully distasteful red carpet choices that will ring it in at the Met Ball on May 6. Sontag said it best when she said: “You can’t do camp on purpose.”