Programming note: For more on fashion and culture, watch the premiere of “American Style” on Sunday, January 13 at 9 p.m. ET.

Fashion is a powerful tool. Covering our bodies in clothes or adornments is an almost universal behavior, and how you dress is one of the most obvious indicators of who you are.

Show me a list of people, and the fashion brands they buy from or engage with, and I could easily produce a series of assumptions about each one. I might make an educated guess about their spending power, or how fashion-conscious they are (or aren’t). I might even be able to give you a sense of their character – at least, I’d feel fairly confident distinguishing the peacocks from the shrinking violets.

Speaking at The Business of Fashion’s Voices conference in the UK on Thursday, data analyst and Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Christopher Wylie took this relatively simple idea to its worrying but logical extension: Like any tool, he said, fashion can become a weapon in the wrong hands.

“Fashion data was used to build AI models to help Steve Bannon build his insurgency and build the alt-right,” he told the conference. “We used weaponized algorithms. We used weaponized cultural narratives to undermine people and undermine the perception of reality. And fashion played a big part in that.”

He would certainly know. As research director at Cambridge Analytica, Wylie used data harvested from 87 million Facebook users to produce algorithms that he says influenced the 2016 US presidential election. And having previously worked toward a PhD in fashion trend forecasting, he knew that someone’s choice of clothing is one of the best ways to unpick their identity.

On stage, Wylie explained how people’s preferences for fashion brands on social media were used to target specific groups with right-wing political messages. Although he has previously divulged how people’s online activity was used to predict political leanings, it was the first time that he publicly detailed fashion’s role – and importance – in Cambridge Analytica’s models.

During his presentation, Wylie showed various charts and graphics demonstrating how the now-defunct firm mapped clothing brands against personality traits.

“There are strong relationships between the brands, style and aesthetics that people engage with, and how they see themselves and their identity,” Wylie said during the talk.

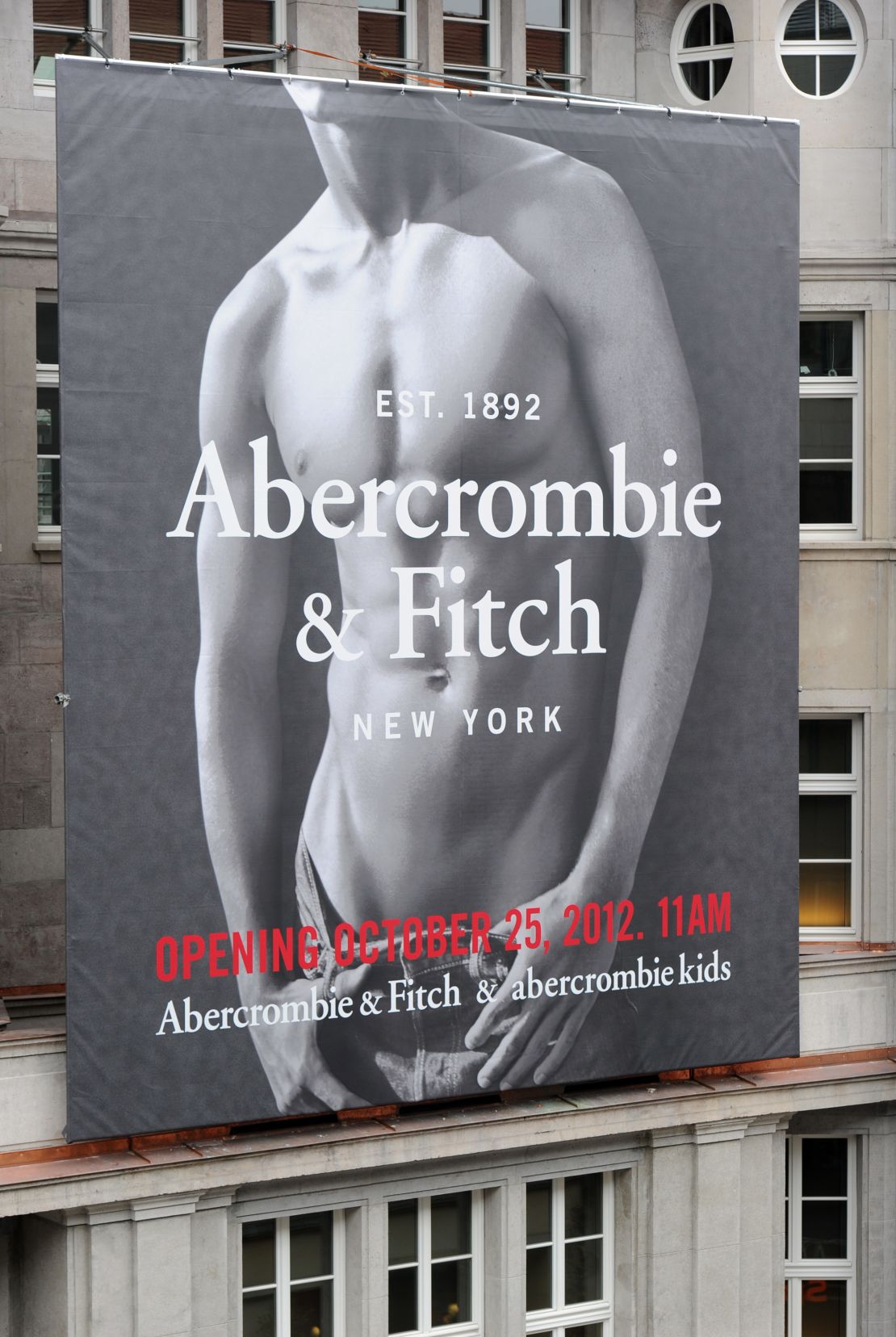

Brands like Wrangler, the jeans company, and the American student favorite Abercrombie & Fitch were compared and contrasted. Wrangler is “more cowboy, older,” and more “modest” than Abercrombie, Wylie said. People who like yoga-wear brand Lululemon “are more extroverted,” while L.L. Bean fans are conscientious but “low in openness.” Other brands featured included Nike, Louis Vuitton, Burberry, Armani, H&M, Elle and Vogue.

The simple, palatable takeaway is that modest, traditional, conventional brands tend to be favored by those with more conservative ideals, while provocative, directional brands, like Kenzo, were more likely to be worn by the liberal-minded.

Targeting vulnerability

The idea that advertisers might target us based on the brands we like, follow, talk about or engage with is hardly new. Nor is the story that Cambridge Analytica used “hyper-profiling” to target different groups for political gain.

More interesting, however, is Wylie’s claim that fashion preferences are statistically among the strongest indicators of our personalities – and that they were a particular focus at Cambridge Analytica.

What makes this especially irksome is the emphasis on specific personality traits. Openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism (the “big five” identified in a psychological model known as OCEAN) were the key traits mentioned.

But others listed in the materials shared by Wylie included depression, anger and vulnerability. In other words, people were being segmented on the basis of their mental stability. Then, if they were considered vulnerable to persuasion, they were targeted with political messaging. This is where the story starts to take on dystopian overtones.

According to Wylie, and as reported by The Business of Fashion, “consulting psychologists encouraged researchers at the firm to ask more questions on aesthetic and stylistic preferences for clothing as they were found to be strong signifiers of traits that were used as a primary means to identify people who were susceptible to joining the alt-right.”

Having helped create what he called – in typically bellicose terms – an “informational weapon of mass destruction,” Wylie then ended his talk by turning responsibility over to the fashion industry. Those in the room had “created the battlefields” of a culture war, he said before directly challenging them to fix the problem.

“We need you guys to do a better job at cultivating our cultural narratives, for our own national security and for the preservation of our democracy,” he said.

“The shame, the colonialism, the racial biases, the toxic masculinity, the fat-shaming that industry puts out – and has been putting out for decades – is exactly what Cambridge Analytica sought to exploit when they were seeking to undermine people and manipulate them.”

The message, in simple terms: Stop making people feel bad, Fashion. It makes them easy targets for untoward digital dealings.

A call to arms

It was difficult to get a sense of how the CEOs and other fashion industry figures in the room felt about Wylie’s rallying cry. There was loud clapping, and most people stood to cheer eventually, but the room didn’t exactly shake. Just hours later, designer Alber Elbaz attracted a more kinetic reaction by ending his own talk by blasting out Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” and dragging people up on stage for a dance.

Did Wylie tell the industry something it already knew? Or is this another case of negative news overload – just another horrible story about the US presidential election and data?

There are, of course, fashion brands that understand how to balance looking good and doing good. Some of them were represented at the conference.

Stella McCartney, for instance, has been working towards sustainability in fashion for nearly 20 years, and she used the event to announce two new green initiatives: A United Nations charter for sustainable fashion, launching officially on December 10 at the UN’s annual climate change conference, and Stella McCartney Cares Green, a new arm of her charity platform.

But whether the fashion industry has the power, or the collective desire, to defend us from the cultural cyber warfare foretold by Wylie, remains to be seen. The fashion world is already tackling a number of troubling issues right now: diversity and inclusion, the treatment of models, human rights in garment factories, sustainability, the fur question. Solving some of these would, indirectly, constitute a start, as it would help craft more positive narratives for brands in need, but the road looks long.

As for Wylie, H&M announced that it has hired him as its director of research. The high street retailer is attempting to use AI and data to optimize its supply chains, with one of the outcomes – if all goes well – being the reduction of textile waste produced by over-ordering. Perhaps, having held a mirror up to the fashion industry, Wylie now has the chance to make amends and take up his own call to arms.