Editor’s Note: Marc Spiegler is the global director of Art Basel, leading its wide-ranging activities across the art world. In June 2016, he joined CNN Style as guest editor, commissioning features on the topic of art and technology.

In 2002, a self-taught programmer named Cory Arcangel hacked the code of a Nintendo Super Mario cartridge, stripping away all the graphics except for the fluffy pixelized clouds.

Two years later, his artwork “Super Mario Clouds v2k3” made Arcangel one of the 2004 Whitney Biennial’s breakthrough stars. Yet many of his new fans, Arcangel once told me, did not really understand what he had done: they thought they were watching a digital video, not hacked software.

A decade later, many people make the same misassumption about the young artist Ian Cheng’s “infinite duration” work, in which his cinematic algorithms live-render richly detailed worlds filled with complex landscapes and animated creatures, “shot” with swooping cameras. Cheng uses radically better software, but it’s the same disconnect…

The history of digital art

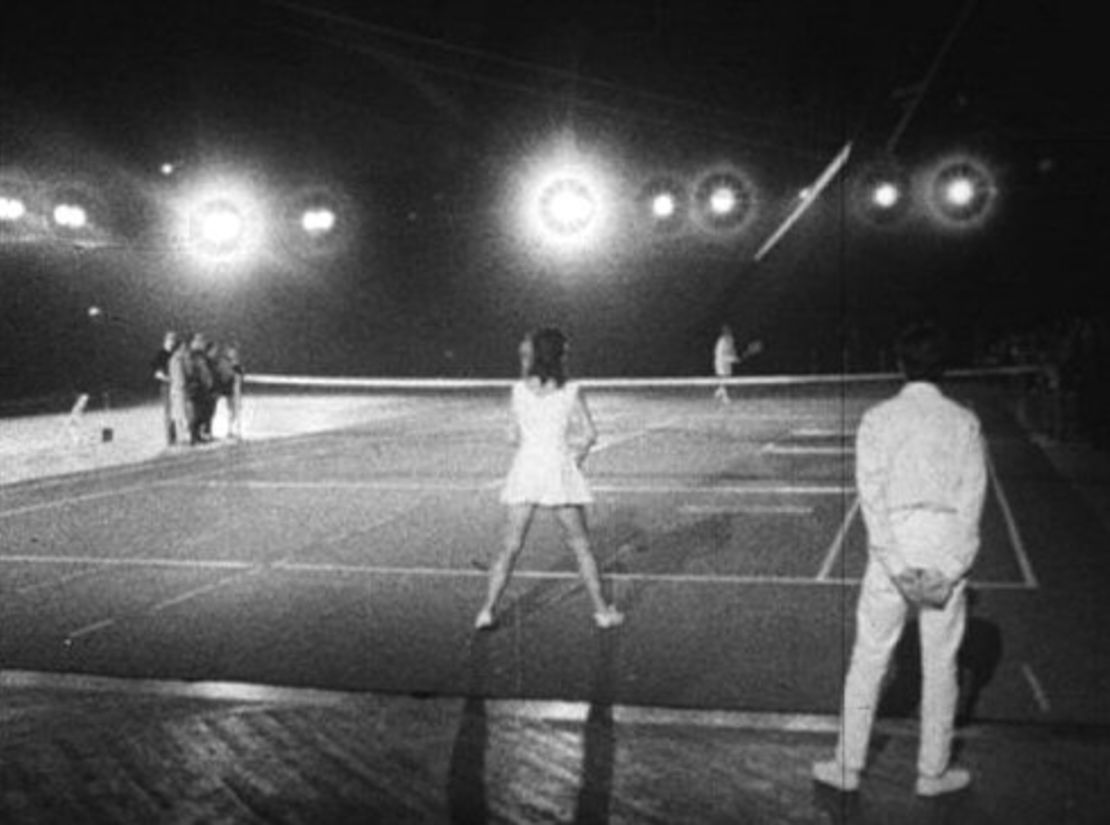

For decades, art and tech have done an awkward, fitful dance, never fully committing to each other. Things started well, 50 years ago: In 1966, Billy Klüver, an engineer at Bell Labs (which later became AT&T) spearheaded Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), putting Bell’s cutting-edge equipment into the hands of artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Merce Cunningham, John Cage and Jasper Johns.

As computers became more sophisticated and widely available, a small group of artists used them in making their work. Yet long after EAT’s experiments, digital art remained an outlier in mainstream museums and galleries, generally sequestered at festivals such as Austria’s Ars Electronica.

For the core of the artworld, most digital art seemed overly enamored with its own technology, and often felt conceptually lightweight.

On the flip side, the digerati dismissed the pieces that the artworld embraced as facile stuff, barely pushing past the basics of the Photoshop toolbox. As someone who loves both art and technology, I despaired for 20 years at the succession of stillborn children that their interactions produced.

Digital-native artists

Finally, my wait has ended: Today the digital work coming out of artists’ studios – often just their laptops - shows a clear shift, dissolving the boundaries between “the art world” and “digital art”.

Why? First, because these young artists are digital natives, who grew up with broadband at their fingertips, and the virtual never far from the physical in their life. (The curators Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Simon Castets label this the “89plus” generation – because 1989 marked the introduction of the World Wide Web.)

Just as importantly, contemporary artists are working with technologies that make it as easy to create digital works as it is to paint or sculpt. That’s not hyperbole: Artists using Tiltbrush technology at the Google Cultural Institute in Paris can sculpt spectacular 3-D volumes in real time by moving their bodies through space, creating a result that looks more organic than digital.

That said, many artists are making work deeply steeped in code. Britain’s Ed Atkins, for example, uses a mix of motion-capture and CGI to create tightly paced videos run through with anomie. Drawing on the dreams and nightmares of the digital age, Atkins unleashes a mix of hooligans, human organs, effluvia and nods to pop culture.

Likewise, the Canadian artist Jon Rafman has become known for his dense VR works. At the Berlin Biennial that opened last week, visitors strapped into an Oculus Rift headset to experience his new piece “View of Pariser Platz.” At first, looking down onto Pariserplatz, the viewer saw nothing different. Suddenly (spoiler alert) reality shifted violently, unleashing visions of billowing smoke, flying bodies, beasts swallowing each other. Then you went into freefall, landing among an army of androids. I watched one woman struggle for balance and contort her hands into tight knots as the digital hallucinations hit her.

Beyond coding

But you don’t need programmers to make digital art today, because social media offers a platform perfect for social engineering.

Amalia Ulman’s controversial “Excellences and Perfections” performance, for example, took place entirely on Instagram over the course of four months in 2014. The Argentine artist created a trajectory in which “she” went from good country girl to urban escort to perfect-lifestyle blogger.

As she spiraled downwards, many of Ulman’s nearly 90,000 followers took the 475 posts at face value and grew increasingly worried for her sanity. (Not that surprising a misunderstanding, really, since on Instagram people’s “real” channels tend to be carefully constructed narratives.)

Thinking more broadly, technology has also redefined the audience for which artists now create. Camille Henrot’s entrancing 2013 Venice Biennale piece ‘Grosse Fatigue,’ for example, was technically possible long ago.

Yet its cascading screens of wildly different videos would have overwhelmed viewers not already accustomed to simultaneously scanning multiple feeds on their phone, tablet, TV, and laptop.

Just as importantly, our ever-more digital society redefines how art is made. Geography becomes less relevant by the day: Artists collaborate with a rotating cast of sparring partners all over the globe, not only other artists, but also writers, coders, fashion designers, electronica musicians, etc.

Much of the content is not created from scratch but rather generated through a voracious sampling, scraping and repurposing of the memes, images and clips that swirl around in the ether.

Copyright seems a tangential issue here. In Berlin last week, I ran into the New Zealand artist Simon Denny standing by his biennial piece – a series of trade-show booths for Blockchain companies.

“Artists make work about the world we live in,” he says. “And in our society, nearly everything involves private companies – even individuals act like brands. So if we want art about the contemporary world and brands are protective of usage and copyright, then how are you supposed to make art today?”

Art market disruption? Not yet

Interestingly enough, especially for someone in my position, there’s one area where technology has had relatively little impact: the art market. At least not in comparison to the way that Uber has totally disrupted the taxi business or that social media forced fashion to radically reconsider the role of runway shows.

The biggest influence on the market so far? Instagram, perfectly designed to make a gallery’s pieces go viral, but not a sales platform per se.

Obviously, the art-market killer app may still come. For now, though, what’s striking about the digital natives is how differently they relate to the market. Because technology allows them to source endless amounts of material, work across time zones, achieve stunning results without any capital, and promote their work directly to their own generation’s curators and collectors.

Can galleries still contribute to the careers of these artists? Absolutely. But many artists choose to dip into and out of the traditional system – or live entirely on its periphery – while focusing less on originality, objects and ownership than on new modes of producing and experiencing art. Finally, the future is now.