Story highlights

"Next Tokyo 2045" presents a future vision of Tokyo that includes a mile-high skyscraper

The proposal shows how coastal cities like Tokyo, can adapt for climate change

Sky Mile Tower faces structural challenges, including water distribution and strong winds

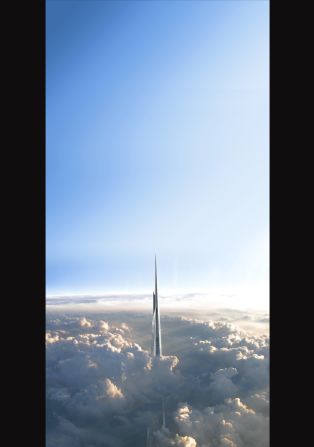

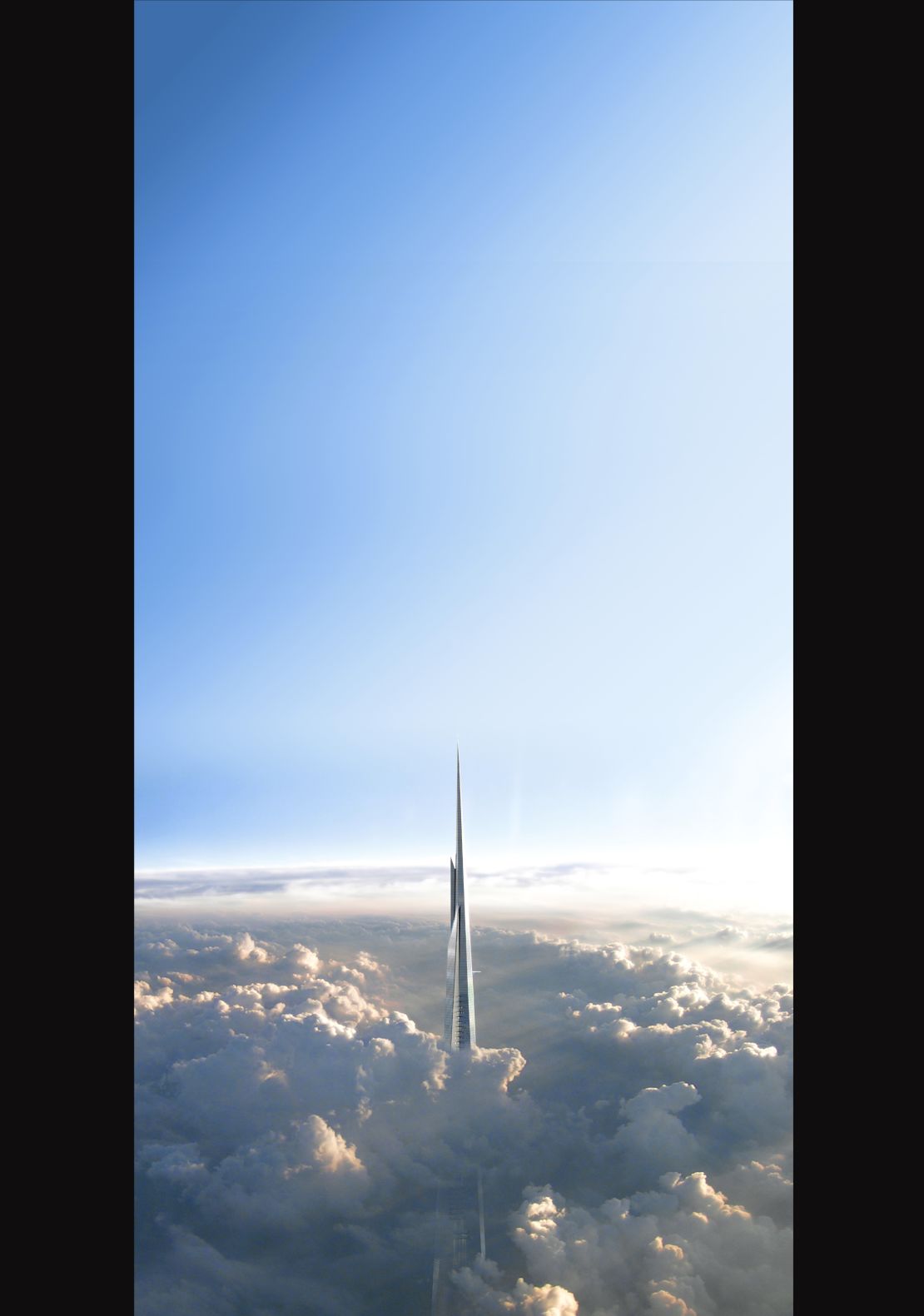

Rising like the Emerald City is a building that will not only dwarf the world’s tallest skyscraper – the Burj Khalifa in Dubai – but double its height.

If built, the aptly named Sky Mile Tower by Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates (KPF) and Leslie E. Roberson Associates (LERA), would climb to approximately 1,600 meters, or one whole mile.

The residential skyscraper is part of “Next Tokyo 2045,” a joint-proposal by the firms for research and developmental purposes. Its intent is to imagine a mega-city that contains resilient infrastructure.

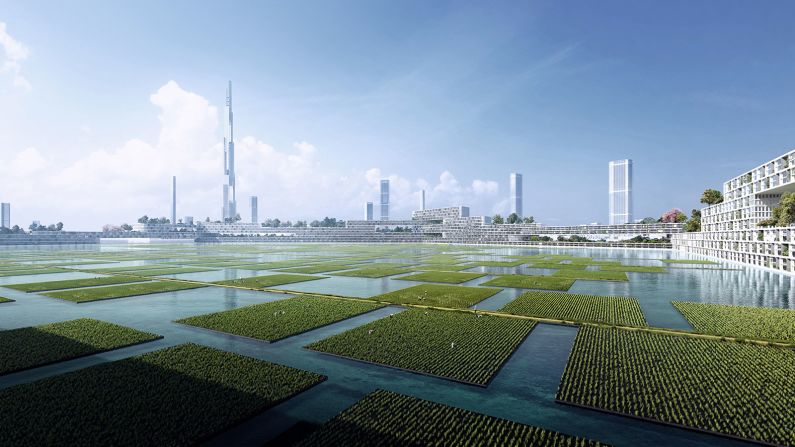

Tokyo, like other vulnerable coastal cities with low-lying elevations, is faced with factors like rising sea levels and increased typhoon risks. The eco-district would be located on reclaimed land in Tokyo Bay and developed for a half-million residents.

“Next Tokyo is a vision for future cities based on challenges we face today,” KPF Principal David Malott told CNN. It was important for the design team that the vision be real: that Next Tokyo can be realized utilizing today’s technologies projected slightly forward into the future.”

Coastal defense strategies

Architectural renderings reveal how the mega-city might address issues like flooding, caused by storm surges. Differently-sized rings (approximately 500 to 5,000 feet in width) shaped like hexagons, are positioned to break up strong waves, while still allowing for ships to pass through. Some doubly function as freshwater reservoirs, others contain urban farming plots.

Structural challenges for a mile-high tower

While there are no plans yet to fund the mega-city or construct the mile-high tower, research into its required technology is outlined in a report released by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH).

The design, intended to house 55,000 occupants, is a response to urban migration trends that forecast the world’s population living in cities to double by 2050. “Next Tokyo explores future urban growth moving upward, rather than outward,” the report says.

At that soaring height, design requirements for wind can exceed those for earthquakes – even, according to the report, in the most earthquake-prone regions of the world. “The tower will naturally have long periods of vibration that will be more readily excited by the wind,” the report explains.

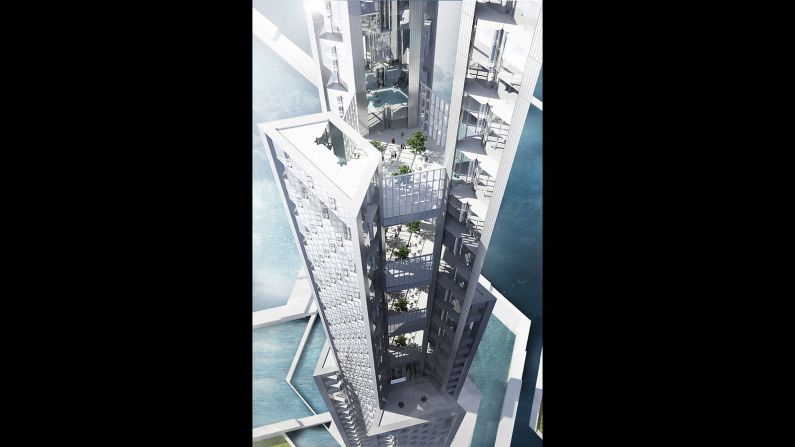

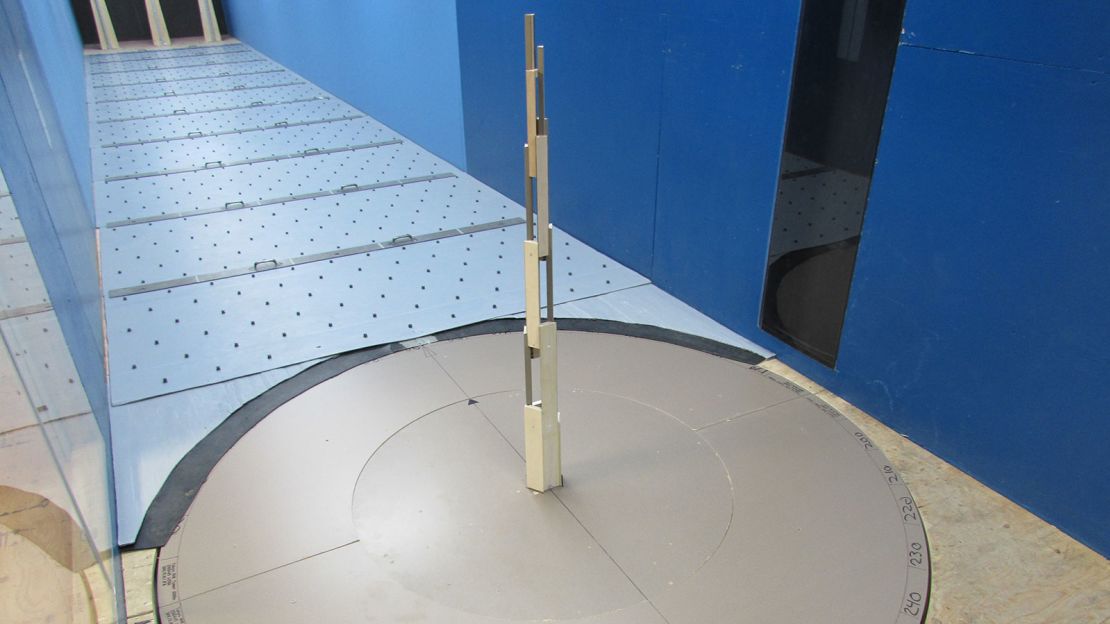

After conducting several exploratory wind tunnel tests, a version of the tower that incorporated incremental steps and tapers, could “confuse the wind” – breaking up large wind vortices which could otherwise amplify the tower’s movements. Vertical slots in the tower’s design allow the wind to flow through.

Water distribution in a mile-high tower is also a challenge highlighted by the report. “Pumping the water directly from the ground would be very costly and time-consuming.”

To solve this, the design uses an articulated facade around the tower’s legs to increase the building’s surface area – which helps facilitate cloud harvesting as a water source. Water would then be collected and stored at different levels of the building.

Building up

Tall, supertall, and now megatall buildings – are on the rise. In January, the completion of 432 Park Avenue in New York marked the world’s 100th “supertall” skyscraper – or those classified by CTBUH as a building over 300 meters (984 feet).

“Megatall” – on the other hand, are buildings over 600 meters (1,968 feet) in height. Three buildings – the Burj Khalifa, the Shanghai Tower, and the Makkah Royal Clock Tower – fit the bill, but four more are under construction and are set for completion by 2021. They include the Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia, which will rise 1-kilometer into the sky.