Since it was discovered in 1922, countless tourists have visited the famed tomb of King Tutankhamun, taking their toll on its historical treasures.

Now, a nine-year conservation project has concluded, returning the tomb to its former glory – and making some intriguing discoveries along the way.

Researchers had feared that moisture and carbon dioxide from tourists’ breath was causing brown spots of microbial growth to spread on the surface of paintings in the burial chamber.

Abrasions and scratches were also accumulating in places where visitors and film crews had access to the small space.

To address the spots and create a sustainable plan for the future of the tomb, the LA-based Getty Conservation Institute and Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities embarked on a conservation collaboration that ended last week.

‘Spots no longer a threat’

King of ancient Egypt at 9, Tutankhamun reigned until his unexpected death at 19, from around 1333 B.C. until around 1323 B.C. His tomb, in the Valley of Kings across the Nile River from Luxor, is famous for having been discovered relatively intact, and for containing thousands of impressive artifacts.

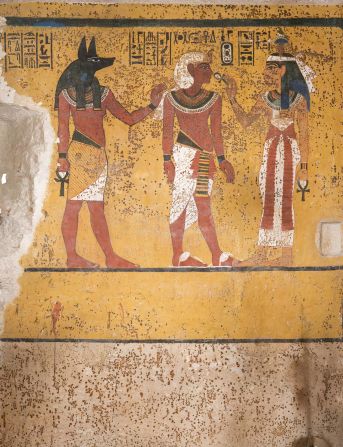

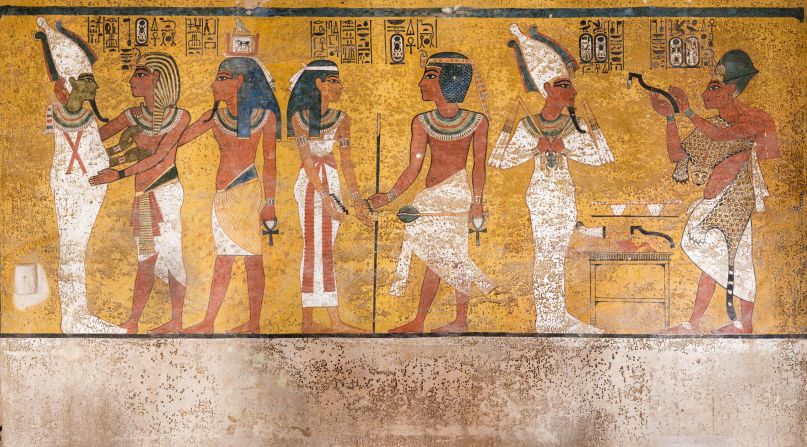

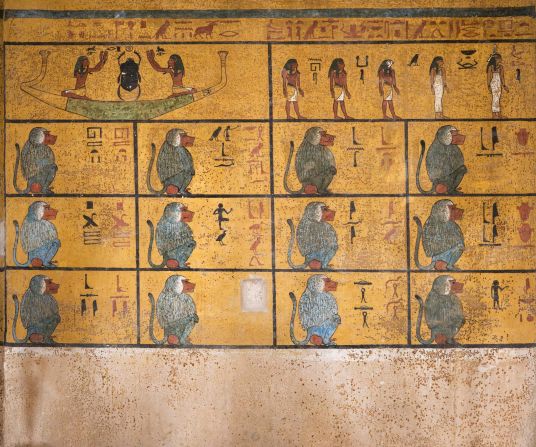

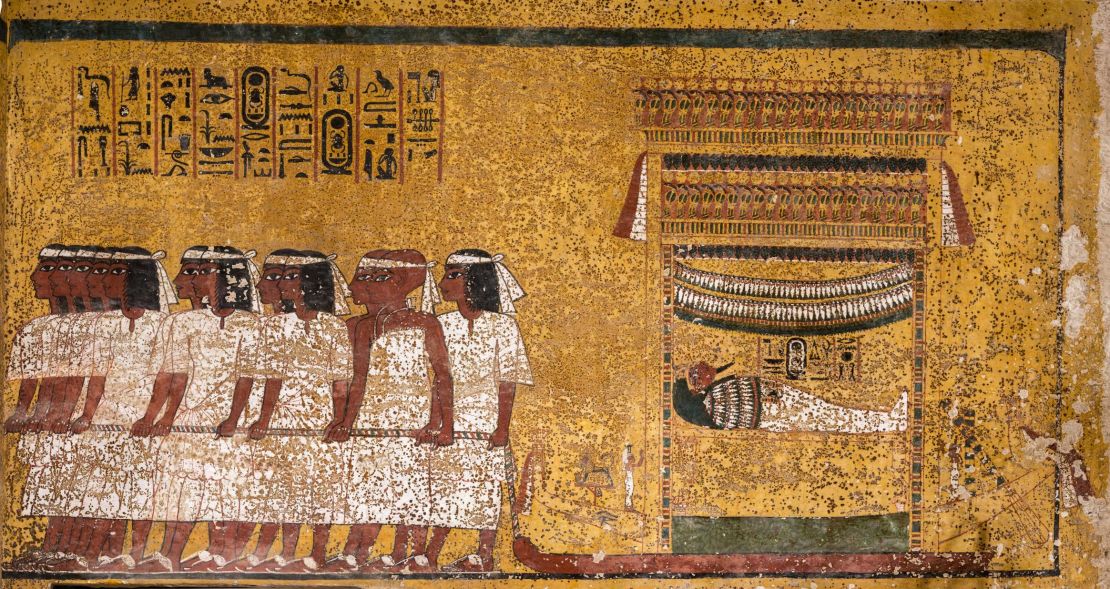

Today, the tomb still contains the mummy of Tut himself, a quartzite sarcophagus, wooden outermost coffin and wall paintings depicting his life and death.

The conservators investigated whether the brown growths were multiplying, active or a danger to the illustrious paintings.

Comparing photographs taken in the 1920s with the current condition of the paintings showed there was no change in the spots. Scientific investigation then concluded that the growths were dead and have fused to the paint layer.

“There is no way we could safely remove them,” said Lori Wong, who worked on the project. “They are no longer a threat to the tomb and probably grew thousands of years ago, soon after the paintings were actually created.”

Clues point to a hasty burial

Early in the restoration work the conservators also found clues that contribute to the hypothesis that Tutankhamun’s death was relatively unexpected, and the tomb was not intended for him. According to Wong, ancient Egyptians likely took a tomb that was already under construction and prepared it for burial – quickly.

As Tut’s tomb is the only Egyptian tomb to suffer from brown spots, there is a possibility that the ancient King’s burial was unusually rushed. It could be that the paint was not dry when the tomb was sealed.

In addition, the space is small and the burial chamber, the most important area in the tomb, is the only chamber that is painted, which is unusual for esteemed Egyptian Kings.

It had been assumed that each wall of the burial chamber would have had the same number of paint layers, but the team found that was not the case. “There is an entire layer missing from one wall that is present on the other three walls,” Wong explained, detailing a further possible sign of haste.

Inbred and sickly?

Contrary to the opulence of Tutankhamun’s burial place, his death may have been more routine. Although the cause of death remains uncertain, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2010 concluded that the King most likely died of malaria, following an infection in his leg.

In 2014, CT scans stitched together to create a “virtual autopsy” shed further light on the pharaoh’s physical condition. They created the first life-size image of Tutankhamun, which showed the ancient King’s left foot was severely deformed. The angle suggests a club foot, which may indicate a rare bone disorder.

Researchers think that this poor health could be attributed to inbreeding because genetic analysis shows that Tutankhamun’s parents were likely siblings.

Conserved for the future

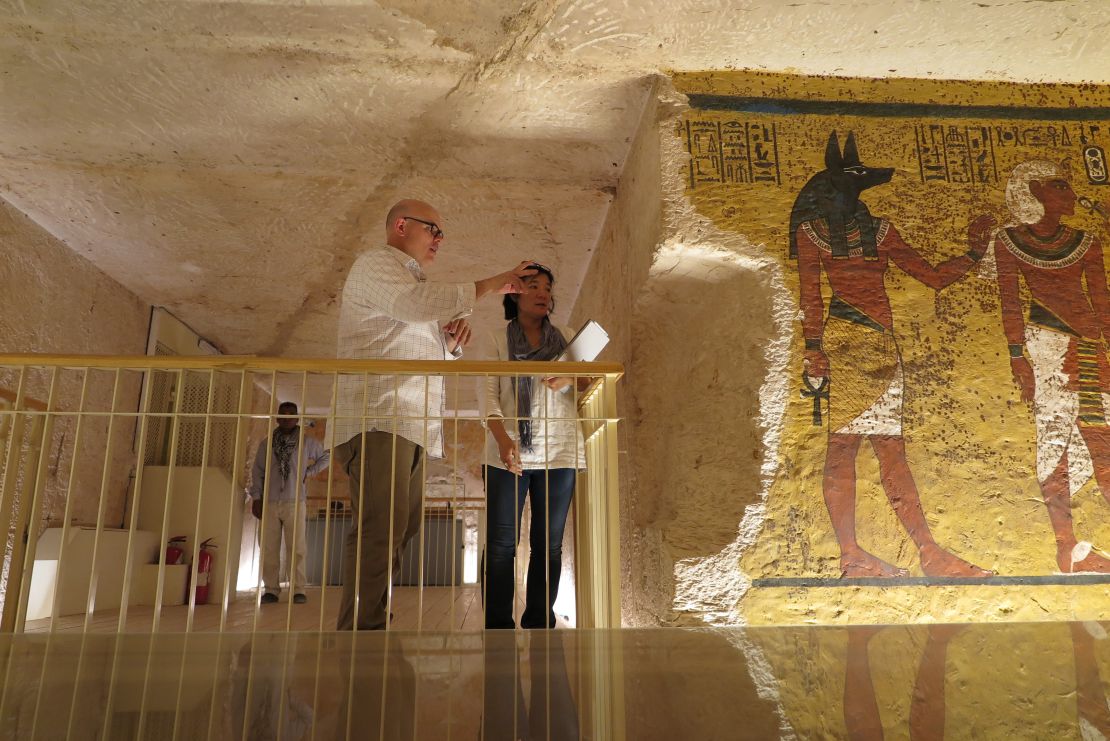

An exact, full-sized replica of Tutankhamun’s tomb was built in Egypt in 2014, but to ensure the real one can remain open as an attraction, the conservators took measures to counter tourist damage. A new viewing platform has been installed, as well as improved walkways, signs, lights, and an air filtration system to combat sweaty visitors and the dust they bring in on their shoes.

“There has to be a high level of good management, maintenance, and care of the tomb in the future,” said Neville Agnew, the project’s leader. “It’s still being used for visitors and benefiting educationally and financially, the Egyptians and the world community.”